Understanding systemic discrimination

We all have the right to be free from discrimination. However, sometimes laws and structures in our society, even when well-intentioned, produce consistently discriminatory outcomes. And what appear to be neutral policies, practices and behaviours may in fact be discriminatory.

Systemic discrimination is a major issue in B.C. and Canada, but it isn’t well understood. Many people wonder, “how can systems be discriminating?” and “how does systemic discrimination really impact people?” Because of this gap in knowledge, some people have experienced systemic discrimination without realizing it and some have unknowingly created or perpetuated discriminatory systems.

The resources on this page—beginning with a video and discussion guide—are designed to address this knowledge gap.

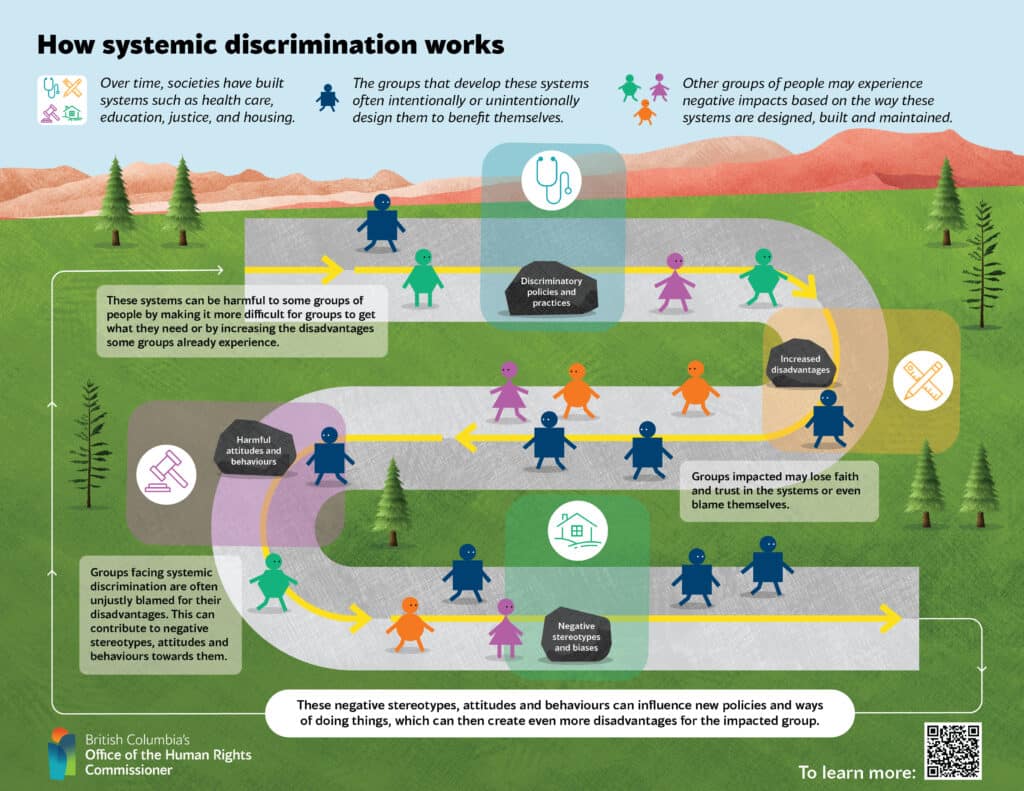

“Systemic discrimination can be defined as patterns of behaviour, policies or practices that create and maintain the power of certain groups over others or reinforce the disadvantage of certain groups.”

How systemic discrimination works

This infographic shows how systemic discrimination is developed, where it occurs, who it harms and how these groups are harmed. Use the infographic to reflect on your community or organization. Where do you see systemic discrimination? Where and how can you act to address it?

A conversation guide and participant handout have been developed to help groups explore the infographic—including schools, organizations and community groups. The companion guide includes pre-conversation activities that will help facilitate conversations that are welcoming, supportive and inclusive for all participants.

Video: Intro to systemic discrimination

Educators! These discussion guides may help kick off conversations with your students or children.

Grades 4–9

Grades 10–12

Systemic discrimination learning modules

BCOHRC offers two webinars on this topic, Introduction to systemic discrimination and Systemic discrimination part 2: What you can do. These learning sessions are also available for individual, self-paced learning. Each session consists of five modules, which focus on specific learning goals and are accompanied by a downloadable PDF of the presentation and a handout package.

Introduction to systemic discrimination

-

Module 1

Introduction

-

Module 2

What is systemic discrimination

-

Module 3

Impacts

-

Module 4

Noticing systemic discrimination

-

Module 5

What can we do?

Systemic discrimination: What we can do

-

Module 1

Introduction

-

Module 2

Importance of taking action

-

Module 3

Identifying an example

-

Module 4

Actions

-

Module 5

Getting started

Examples of impacts of systemic discrimination

These statistics and quotes are examples of how systemic discrimination harms specific groups within different systems.

The examples highlight how different groups experience more barriers or harm based on their personal characteristics, such as disability or age. These examples are provided to raise awareness of how policies (or lack of policies), practices and behaviours within an organization contribute to systemic discrimination.

One of the unfortunate consequences of speaking about the harms caused by systemic discrimination is that the harm can become attributed as a characteristic of the harmed group. For example, some people might wrongly assume that women are less hard working than men when they read the statistic below showing that, on average, women earn 68 per cent the salary of men. When reading the examples below, reflect on which policy, practice, attitude or behaviour might cause the negative impacts each group experiences.

Systemic discrimination in the education system

Impact on Indigenous Peoples and people with disabilities

For example:

92.1% of all students graduate with a certificate of graduation or adult graduation diploma within six years of enrolling in grade 8, compared to 77.6% of students with disabilities and 73.7% of Indigenous students.1

Impact on LGBTQ2SAI+ people

For example:

62% of LGBTQ2SAI+ students across Canada feel unsafe in schools. 2

Here is how one Black student described how systemic discrimination in the education system impacted them:

“As a black student, when the first thing I see when I walk into school in the morning is an armed police officer, it automatically gives me the message that ‘you aren’t really welcome.’” 3

— Vancouver student

To learn more about systemic discrimination in schools, visit pages 30 to 36 of the Rights in Focus report.

Systemic discrimination in employment

Impact on women

For example:

On average, women in B.C. earn $0.68 for every dollar earned by men. 4

Impact on elders

For example:

63% of jobseekers aged 45 and older are unemployed for more than a year, compared to 36% of people aged 18 to 24.5

Here is how one Indigenous person described how systemic discrimination in the workplace impacted them:

“Being Aboriginal, we don’t get hired in a lot of places. I’ve applied everywhere in the past 30 years, and I’ve only received about three jobs.… They told me [to] go back to the reserve.” 6

To learn more about systemic discrimination in employment, visit pages 36 to 44 of our Rights in Focus report.

Systemic discrimination in the health care system

Impact on Indigenous Peoples

For example:

In a survey, 84% of Indigenous Peoples reported experiences of discrimination when receiving health care services in B.C.7

Impact on the basis of poverty

For example:

B.C. residents in the lowest income group experience more than double the rate of treatable deaths and nearly triple the rate of preventable deaths than people in the highest income group.8

For definitions for treatable deaths and preventable deaths, consult our glossary.

Here is how one Indigenous person described how systemic discrimination in the health care system impacted them:

“When somebody has to go to the emergency room and gets sent home right away, nobody is surprised in my family. We get asked immediately, ‘Are you on drugs?’ ‘Are you high?’ ‘Why are your eyes red?’ All these questions that are just not appropriate, rather than: ‘What’s going on?’ and ‘What do you need help with?’” 9

— Pamela Beebe, Indigenous rights activist

To learn more about systemic discrimination against Indigenous Peoples in health care, see pages 44 to 51 of our Rights in Focus report.

Systemic discrimination in housing

Impact on LGBTQ2SAI+ people

For example:

LGBTQ2SAI+ individuals make up 4% of B.C.’s population but 11.3% of individuals identified in B.C.’s 2023 point-in-time homeless count.10

Impact on people with physical and mental disabilities

For example:

Over two-thirds (69%) of participants in B.C.’s 2023 point-in-time homeless count reported multiple health conditions, including acquired brain injuries (33%) and physical disabilities (41%).11

Here is how one parent of a child with a disability described how systemic discrimination in the housing system impacted them:

“We applied to so many places and only one person, because my son (has) special needs and has a wheelchair, would let us even look at the place.” 12

Systemic discrimination in the child welfare system

Impact on Indigenous Peoples

For example:

Despite making up only 10% of the population, 68% of children and youth in care are Indigenous.13

Impact on people with disabilities

For example:

Over half of court decisions regarding continuing custody orders involve children with disabilities.14 In some cases, when parents indicate they need assistance, this need is used against them by decision makers as evidence that they are not capable caregivers.15

Here is how one person with a disability described how systemic discrimination in the child welfare system impacted them:

“Mothers and fathers are losing their children to the Ministry [of Children and Families] simply because they cannot find housing for themselves and their family. Facing homelessness and losing children due to a chronic health disability and lack of affordable housing is one of the greatest human rights issues I have ever seen.” 16

Systemic discrimination in the social safety net

Impact on women

For example:

Nearly half (44%) of women in Canada have experienced some form of intimate partner abuse, whether physical, sexual, psychological or emotional.17

Impact on Indigenous Peoples, persons with disabilities and LGBTQ2SAI+ people

For example:

Rates of gender-based violence are higher for Indigenous women, women with disabilities, sexual minority women, trans women and gender diverse people and women living in rural communities.18

Here is how one Indigenous woman described how systemic discrimination in the social safety system impacted her:

“Indigenous women … we have gone through perhaps, years of trauma … and have witnessed police brutality against our family members … and in the case where we are sexually assaulted or abused … we feel very scared to be cared for medically, very afraid to call police as sometimes police have been the perpetrators of said abuse … and it’s very hard for us to seek assistance when we do not have a level of trust … that our bodies will not be put in any more harm and that our rights will be upheld.” 19

To learn how systemic discrimination contributed to anti-Asian hate crimes during the COVID-19 pandemic, see pages 42 to 50 of our From Hate to Hope report.

Systemic discrimination in the justice system

Impact on Indigenous Peoples

For example:

On any given day in 2023, about 1829 individuals were in B.C. correctional centres and 36% of them identified as Indigenous.20

Impact on people with mental disabilities and/or addictions

For example:

In B.C., about 67% of incarcerated people have a mental health or substance use disorder and over one-third have both.21

Here is how one racialized parent described how systemic discrimination in the justice system impacts her family:

“Right now, I’m scared for my son. One day he will become a Black man. I don’t know when that happens, but I know I will not be able to protect him…. I know that because of his Blackness, he is more likely to be killed during police intervention. If that sentence feels strictly statistical to you, take a moment and realize that I am talking about my son, the little boy who still howls ‘mama’ when he’s feeling vulnerable.” 22

To learn how systemic discrimination impacts Indigenous and racialized communities in policing, see our Equity is Safer report.

Systemic discrimination in the response to climate change

Impact on Indigenous Peoples

For example:

42% of wildfire evacuations occur in Indigenous communities.23 Other adverse effects include increased risks of floods and fires, lower food productivity, loss of biodiversity and destruction of wildlife habitat.24

Impact on elders

For example:

The BC Coroners Service identified 569 heat-related deaths from June 20 to July 29, 2021, 445 of which occurred during the heat dome. Of those who died, 79% were 65 years of age or older.25

Here is how one Indigenous person described the impact of colonial land use laws and practices:

“You have this criminalization of Indigenous land defenders; it’s not just civil disobedience for breaking colonial laws, it’s criminalization for following our own laws, like following the laws of our Nations and our People. It’s actually a legal requirement in our systems to protect the land for the next seven generations or whatever the teachings may be in your nation. By upholding our laws, we are being criminalized … [as] a result of us trying to protect our land for future generations.” 26

-

Learn about which groups are protected from systemic discrimination and where they are protected under B.C.’s Human Rights Code.

-

Register for the free, 90-minute webinars, Introduction to systemic discrimination and Systemic discrimination: What we can do.

-

Learn about our Xenon 2 immersive education experience and request an in-person session for your workplace or organization.

Sources

- Education Analytics Office. “BC Schools – Six-Year Completion Rate.” British Columbia Data Catalogue. Accessed June 21, 2024. https://catalogue.data.gov.bc.ca/dataset/bc-schools-six-year-completion-rate.

- Peter, Tracey, Christopher P. Campbell, and Catherine Taylor. Still In Every Class In Every School: Final Report on the Second Climate Survey on Homophobia, Biphobia, and Transphobia in Canadian Schools. Toronto, ON: Egale Canada Human Rights Trust, 2021. https://indd.adobe.com/view/publication/3836f91b-2db1-405b-80cc-b683cc863907/2o98/ publication-web-resources/pdf/Climate_Survey_-_Still_Every_Class_In_Every_School.pdf.

- Argyle Communications, School Liaison Officer: Student and Stakeholder Engagement Program, (Vancouver: Argyle Communications, 2021), 26, https://www.vsb.bc.ca/News/Documents/VSB-SLO-EngagementReport-Mar2021.pdf.

- Drolet, Marie and Mandana Mardare Amini. “Intersectional perspective on the Canadian gender wage gap.” Studies on Gender and Intersecting Identities, Statistics Canada. Last updated September 21, 2023. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/ n1/pub/45-20-0002/452000022023002-eng.htm.

- Rodriguez, Jeremiah. “It’s harder for Gen-X, people aged 45 and older to land jobs, new study finds.” CTV News, July 28, 2021. https://www.ctvnews.ca/lifestyle/article/its-harder-for-gen-x-people-aged-45-and-older-to-land-jobs-new-study-finds/.

- Anonymous Baseline focus group participant from Cranbrook, April 3, 2023. Quoted in British Columbia’s Office of the Human Rights Commissioner. Human Rights in Cranbrook. British Columbia’s Office of the Human Rights Commissioner, 2024. https://baseline.bchumanrights.ca/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/BCOHRC_Cranbrook-Brief.pdf.

- Turpel-Lafond, Mary Ellen. In Plain Sight: Addressing Indigenous-specific Racism and Discrimination in B.C. Health Care. Addressing Racism Review, 2020. https://engage.gov.bc.ca/app/uploads/sites/613/2020/11/In-Plain-Sight-Full- Report-2020.pdf.

- Rasali, Drona, Diana Kao, Daniel Fong, and Laili Qiyam. Priority Health Equity Indicators for British Columbia: Preventable and Treatable Premature Mortality. Vancouver, B.C.: BC Centre for Disease Control, Provincial Health Services Authority, 2019. http://www.bccdc.ca/Our-Services-Site/Documents/premature-mortality-indicator-report.pdf.

- Yourex-West, Heather. “Evidence of racism against Indigenous patients is growing: Is a reckoning in Canadian health care overdue?” Global News, Jan. 19, 2022. https://globalnews.ca/news/8523488/evidence-of-racism-against-indigenous-patients-is-growing-is-a-reckoning-in-canadian-health-care-overdue/.

- Homelessness Services Association of BC, James Caspersen, Stephen D’Souza, and Dustin Lupick. Report on Homeless Counts in BC: 2023. Burnaby: BC Housing, 2024, 49. https://www.bchousing.org/sites/default/files/media/ documents/2023-BC-Homeless-Counts.pdf.

- Homelessness Services Association of BC et al. Report on Homeless Counts in BC: 2023.

- Anonymous Baseline focus group participant in Cranbrook, February 23, 2023. Quoted in British Columbia’s Office of the Human Rights Commissioner. Human Rights in Cranbrook.

- Ministry of Child and Family Development. “Performance Indicators.”; Statistics Canada. “Table 98-10-0293-01 Indigenous identity population by gender and age: Canada, provinces and territories, census divisions and census subdivisions.” Last updated November 15, 2023. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=9810029301

- Mosoff, Judith, Isabel Grant, Susan B. Boyd, and Ruben Lindy. “Intersecting Challenges: Mothers and Child Protection Law in BC.” UBC Law Review 50, no. 2. (2017): 435. https://commons.allard.ubc.ca/fac_pubs/168/.

- Mosoff et al. “Intersecting Challenges”; Track. Able Mothers.

- British Columbia’s Office of the Human Rights Commissioner. Provincial Survey of Service Providers. June 2023.

- Statistics Canada. “Intimate partner violence in Canada, 2018: An overview.” Accessed June 3, 2024. https://www150. statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/85-002-x/2021001/article/00003-eng.htm.

- Canadian Women’s Foundation. Until All of Us Have Made It: Gender Equality and Access in Our Own Words. Canadian Women’s Foundation, 2020. https://canadianwomens.wpenginepowered.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/101_ MMB_CWF_Whitepaper_V-Final-HiRes_May29_2020.pdf.

- Anonymous Baseline interview participant in Terrace, February 9, 2023.

- Ministry of Public Safety and Solicitor General. “BC Corrections Adult Custody Statistics.” Last updated May 1, 2024. https://app.powerbi.com/view?r=eyJrIjoiNzE2ZmM5MTMtN2U5ZC00ZGQ1LTk4YWUtY2UwNDdiYWI5NTQyIiwidCI6 IjZmZGI1MjAwLTNkMGQtNGE4YS1iMDM2LWQzNjg1ZTM1OWFkYyJ9&pageName=ReportSection69506dda63e5b44 60c64

- Government of British Columbia. Profile of BC Corrections. Government of British Columbia, 2023, 10. https://www2. gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/law-crime-and-justice/criminal-justice/corrections/reports-publications/bc-corrections-profile. pdf. Other research tracking mental health intake forms completed on admission to B.C. provincial prisons found a large increase in the proportion of people with mental health or substance use disorders, from 61 per cent in 2009 to 75 per cent in 2017. See Butler et al. “Prevalence of mental health needs.”

- McKinnon, Audrey. “My little boy will grow up to be a Black man — and I’m afraid”. CBC News, Jun. 14. 2020, https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/my-little-boy-will-grow-up-to-be-a-black-man-and-i-m-afraid-1.5610551.

- Lewis, Haley. “42% of wildfire evacuations occur in Indigenous communities, researcher.” Global News, August 25, 2023, https://globalnews.ca/news/9918749/indigenous-vulnerable-wildfires-evacuations/

- Gifford, Robert and Craig Brown. “British Columbia chapter.” In Canada in a Changing Climate: Regional Perspectives Report, edited by Warren, F.J., N. Lulham, and D.S. Lemmen. Government of Canada, 2022, 11-23. https://changingclimate.ca/site/assets/uploads/sites/4/2020/11/ British-Columbia-Regional-Perspective-Report-.pdf. Ford, James, Laura Cameron, Jennifer Rubis, Michelle Maillet, Douglas Nakashima, Ashlee Cunsolo Willox, and Tristan Pearce. “Including indigenous knowledge and experience in IPCC assessment reports.” Nature Climate Change 6, (2016): 349–353. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate2954

- BC Coroners Service. Extreme Heat and Human Mortality: A Review of Heat-Related Deaths in B.C. in Summer 2021, 2022. https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/birth-adoption-death-marriage-and-divorce/deaths/coroners-service/death-review-panel/extreme_heat_death_review_panel_report.pdf.

- Justice for Girls. “Justice for Girls & BCOHRC Indigenous Rights & Environmental Justice Dialogue Overview” (unpublished report, 2024).