Disclaimer:

This summary highlights key learnings from Section 5 of the report. Download our full report (PDF, 23MB) for more information and details. You may also click on a heading below to open up that section of the PDF report.

Hate incident reporting

The Inquiry survey showed most people who experience or witness hate do not report what happened. Most say they did not report it because they didn’t think reporting it would make any difference. Some people are afraid of what would happen if they made a report. People who do report hate often say that the response wasn’t helpful.

-

People don’t report to the police where the police are feared or distrusted. The process for reporting to the police can be hard to find and follow. Vancouver has the only police department in B.C. where reports can be made online and in many languages. The police often say that what happened is not a crime so there is nothing they can do.

-

More communities are creating ways for people to report hate to the community. These options may be more trusted than police and may be better able to support the person who is making the report. This type of reporting can collect more information about hate in the community.

-

This network of community organizations receives funding from the government to help stop racism in B.C. They often hear reports of hate, but most do not have the resources to track reports or support the person making the report.

-

Many B.C. government offices don’t have policies to identify and respond to hate and don’t collect information on hate.

-

Students experiencing hate in schools often don’t know where to report it or are afraid their report won’t be taken seriously. There is a way to report anonymously online through ERASE (Expect Respect and a Safe Education). University students are also often unwilling to report hate to their university.

-

The government announced plans to create a new hotline in April 2021, but hasn’t said when it will be built.

In order to work well, ways to report should:

- offer many ways to report, such as by phone, email or apps

- have different language options or translation services

- receive reports from those who experienced hate but also from those who see hate happen, community members and service providers

- allow people to report without giving their name

- collect as many details as possible about what happened

- include options to share photos, videos or audio

- give information about supports available to the person making the report

- never forward reports to the police unless the person making the report agrees

- include a “quick exit” button for people who need to hide their report quickly

- respond to reports directly and quickly

“There are incredible social consequences for speaking out.”

— Respondent to the Commissioner’s public survey

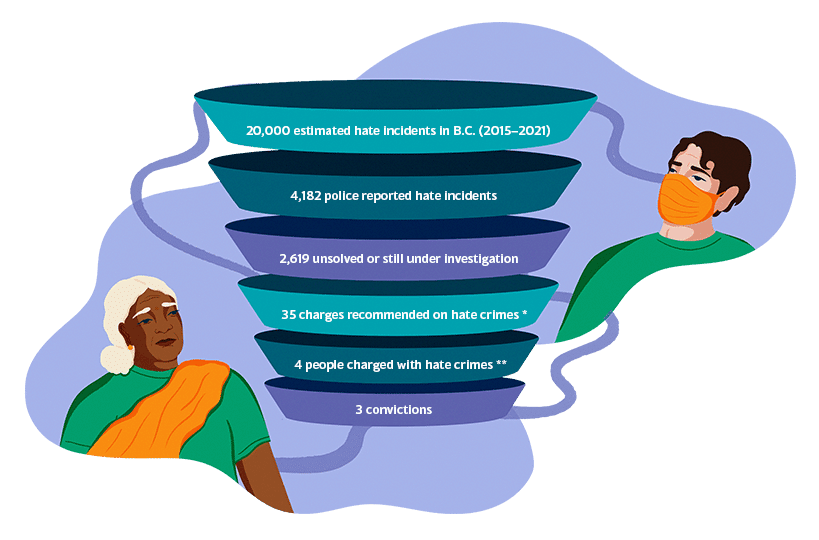

*this includes charges recommended under ss. 318(1), 319(1), 319(2), and 430(4.1) of the Criminal Code. This does not include charges for other offences that may be motivated by hate. This number is not tracked.

** this includes approved charges under ss. 318(1), 319(1), 319(2), and 430(4.1) of the Criminal Code. This does not include charges for other offences that may be motivated by hate. This number is not tracked.

Legal system responses

There are different laws that work to prevent or respond to hate.

International human rights laws uphold:

- the right to freedom from discrimination for everyone

- protection for specific groups such as women or people with disabilities

- prevention of genocide

- protection against hate speech

Canada’s Criminal Code prohibits:

- hate speech in a public way or place

- mischief to religious or educational property

- hate propaganda made available to the public

Other crimes might also be motivated by hate. This can impact what punishment is given to someone who is convicted of a crime. If it is proven that the crime was motivated by hate, the punishment can be increased.

Police departments receive and investigate reports about hate. Only some police departments have teams or positions dedicated to this work. The BC RCMP Hate Crimes Team is a resource for all police departments in B.C. and coordinates data, investigations, tracking and communications about hate crimes.

Under the Criminal Code the following steps result in a person being convicted of a hate crime:

- The police decide if charges are recommended.

- The Crown lawyer (prosecutor) decides whether to approve the charges.

- At a trial, the Crown lawyer presents all relevant evidence and arguments.

- At a trial, the defence lawyer responds to what the Crown lawyer presented and/or presents other evidence and arguments.

- The Crown lawyer must prove the person is guilty beyond a reasonable doubt.

- The judge decides if the person is guilty or not. The person is presumed innocent until proven guilty.

- If the judge decides a person is guilty, the judge sentences the person to sanctions such as prison time or fines.

- A judge can increase a person’s sentence if they are found guilty of a crime that is motivated by hate.

It can be hard to prove that someone committed a hate crime and that hate is a motivating factor when someone commits a crime.

Administrative law

B.C.’s Human Rights Code protects against hate speech. People who have experienced hate speech can make a complaint to the Human Rights Tribunal. If the Tribunal finds someone has used hate speech, the Tribunal can order remedies such as ordering them to stop or ordering payment to the victim. The Tribunal cannot send anyone to prison.

Some limits of the Human Rights Code include:

- Only some parts of a person’s identity are protected. For example, hate directed at someone because they are poor is not against the law.

- Only hate expressed in certain situations is protected. For example, something hateful said to a stranger on the street is not against the law.

- In the Commissioner’s view, online hate is covered by the Human Rights Code. We recommend that this be made clearer in the law.

- The complaint must be made within one year of the hate happening.

- It may be difficult to get legal help with a complaint.

- The Tribunal has been underfunded so there have been long delays. The Tribunal received additional funding in January 2023.

Civil law

B.C. legislation includes references against hate in laws such as:

- Multiculturalism Act

- Corrections Act Regulation

- Youth Custody Regulation

- Security Services Regulation

- Civil Rights Protection Act

The Civil Rights Protection Act applies across B.C. to a wide range of people, but is rarely used.

Support for victim-survivors of hate

People, families and communities who experience or witness hate need support. Over 400 service providers offer support to victims in B.C., but these services are not designed especially for victim-survivors of hate. They do not usually serve families and communities impacted by hate.

Community groups create supports for people who experience or are impacted by hate. People are more likely to share their experiences and look for support with people and groups they already trust.

Many people do not know how or where to find support or services after experiencing hate. Often the service is not provided in their language or with understanding of their culture. Sometimes services are delayed; when people can’t access support, they quickly become more isolated.

Community organizations have done so much work supporting people through the pandemic, but they do not have enough funding or resources. People providing these services need training and protection from burn-out.

Inquiry report (full)

The full Inquiry report (PDF, 23MB) is available for download. The over 400-page-long report (including appendices) details the Inquiry process, community stories, investigation results and the Commissioner’s recommendations for how we can collectively move forward.

For a quick overview, see the plain language summaries below or our executive summary, also available in multiple languages.