Disclaimer:

This summary highlights key learnings from Section 3 of the report. Download our full report (PDF, 23MB) for more information and details. You may also click on a heading below to open up that section of the PDF report.

What are the root causes of hate?

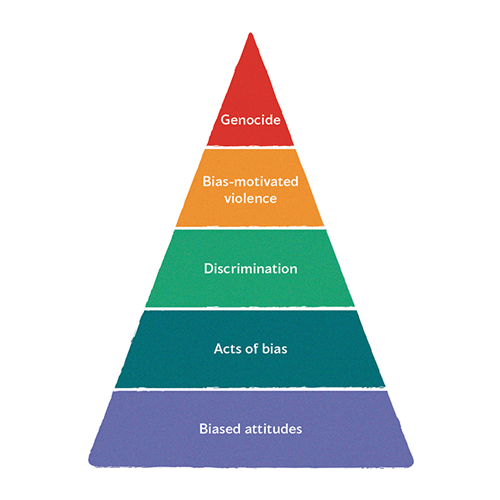

Hate is based in issues of power and control.

Hate comes from the idea that certain people can or should have power and control over others. These ideas come from our history where certain people took power over others. These ideas are built into systems that help certain people keep their power.

Hate starts from negative assumptions, images and beliefs about a certain group. These negative assumptions are called stereotypes. In times of crisis, stereotypes can become stronger and lead to hate toward members of a group. For example, during the pandemic, beliefs about diseases coming from Asia increased hate against Asians.

Hate has always existed in our province but it has increased during the COVID-19 pandemic.

“The hate that has always been there is no longer skulking in dark corners, as it were. Now, it’s out there. Hate and the people who spread it have kind of gone mainstream. It’s no longer considered to be taboo…”

— Respondent to the Commissioner’s public survey

Why do hate incidents happen?

Most people feel stress, fear and anxiety in a pandemic. But many people don’t say or do hateful things. It’s important to understand why some people act hatefully so that we can work to stop this from happening.

When there is a crisis, some people feel defensive and blame other people and groups. When someone sees a group as a threat, it might lead them to act or speak hatefully to members of that group.

- They might show hate to defend the way things are and stop change from happening.

- Acting out hateful ideas can also help some people be accepted by their peer group.

- They may feel they are getting revenge because they feel attacked.

- Some people do and say hateful things because they are part of a group that is trying to exclude, hurt or even destroy a group of people.

Some ways the pandemic led to an increase in hate:

-

Money-related stress—such as losing work or having trouble paying the bills—may increase hate. People may think another group has an unfair advantage that threatens their jobs, homes or community.

-

Community and belonging are especially important during times of crisis. When people feel disconnected and alone, they are more likely to be attracted to hate-based ideas and groups where they feel they can belong.

-

Before and during the pandemic, it has become more common to hear hateful things in the news or online and to hear politicians or famous people saying hateful things. This can make hate seem more normal, which makes it easier for people to say or do hateful things and makes it harder to stand up against hate.

-

Anxiety and fear about the pandemic have led some people to blame Asians for the virus. Having someone to blame can help people feel they can explain and control a scary situation. This happened during other pandemics in history as well.

-

-

Measures such as rules about lockdowns, masks and vaccines led to an increase in hate. People who felt anxious or distrustful of the government’s decisions found it easier to believe conspiracy theories and extreme views. Many people spent more time alone and online during the pandemic. More time online made it easier to hear hateful ideas and connect with people who are encouraging hate. Increased use of alcohol and drugs have also contributed to the rise in hate.

-

Misinformation (sharing wrong information without meaning to), disinformation (sharing wrong information on purpose) and conspiracy theories (explanations that blame government or certain groups) have all increased during the pandemic.

-

These groups have grown during the pandemic. They share hateful ideas and disinformation online to increase feelings of distrust and hate.

-

Misogyny is hatred against women. Many men involved in hate-based groups speak and act in hateful ways against women.

-

Hate-based groups work hard to add new members to their groups. Online, they target people who are vulnerable, such as children or youth and adults who experienced trauma as children.

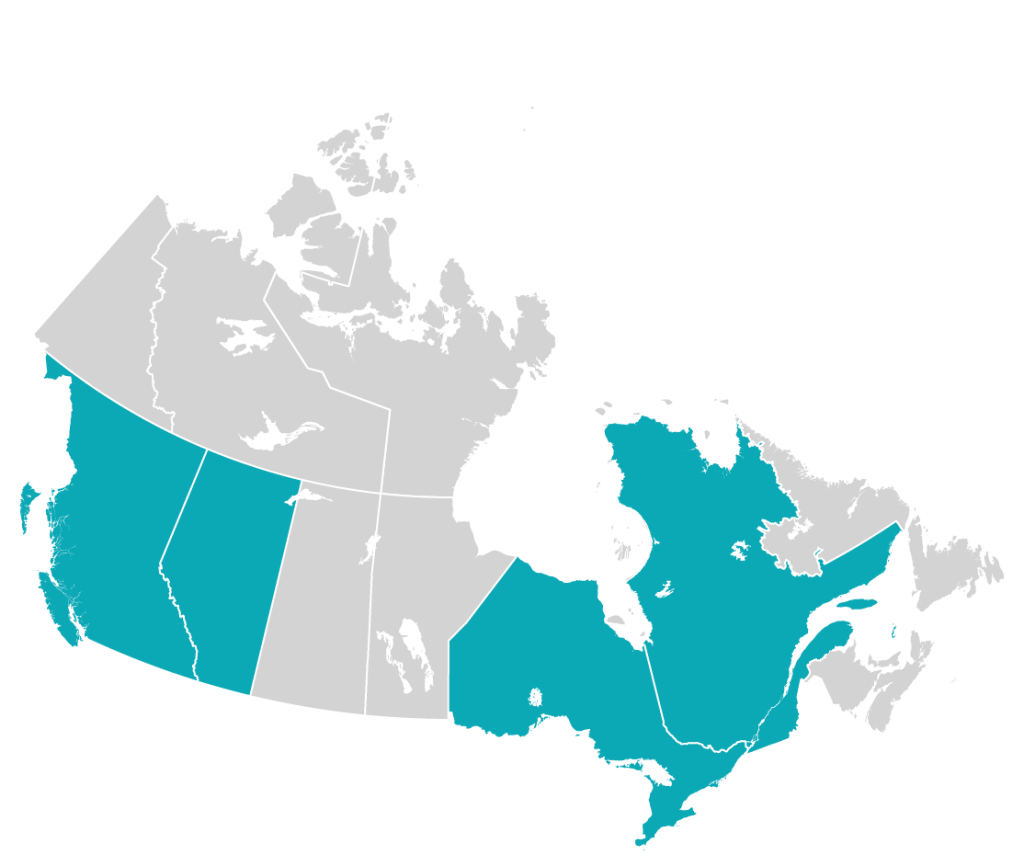

About 300 far-right extremist groups have emerged in Canada since 2015, and are primarily located in Ontario, Quebec, Alberta and British Columbia.

Source: The Standing Committee on Public Safety and National Security, June 2022

Inquiry report (full)

The full Inquiry report (PDF, 23MB) is available for download. The over 400-page-long report (including appendices) details the Inquiry process, community stories, investigation results and the Commissioner’s recommendations for how we can collectively move forward.

For a quick overview, see the plain language summaries below or our executive summary, also available in multiple languages.